- Home

- Robert Ervin Howard

Almuric Page 11

Almuric Read online

Page 11

"It is well. Now to this other matter. Have you the parchment?"

"Aye."

"Then I will sign it. Give me the stylus."

I heard the crackle of papyrus and the scratch of a keen point, and then the Queen said:

"Take it now, and lay it on the altar in the usual place. As I promise in the writing, I will appear in the flesh tomorrow night to my faithful subjects and worshippers, the blue pigs of Akka. Ha! ha! ha! I never fail to be amused at the animal-like awe on their stupid countenances when I emerge from the shadows of the golden screen, and spread my arms above them in blessing. What fools they are, not in all these ages, to have discovered the secret door and the shaft that leads from their temple to this chamber."

"Not so strange," grunted Gotrah. "None but the priest ever comes into the temple except by special summons, and he is far too superstitious to go meddling behind the screen. Anyway, there is no sign to mark the secret door from without."

"Very well," answered Yasmeena. "Go."

I heard Gotrah fumbling at something, then a slight grating sound. Consumed by curiosity, I dared open one eye a slit, in time to glimpse Gotrah disappearing through a black opening that gaped in the middle of the stone floor, and which closed after him. I quickly shut my eye again and lay still, listening to Yasmeena's quick pantherish tread back and forth across the floor.

Once she came and stood over me. I felt her burning gaze and heard her curse beneath her breath. Then she struck me viciously across the face with some kind of jeweled ornament that tore my skin and started a trickle of blood. But I lay without twitching a muscle, and presently she turned and left the chamber, muttering.

As the door closed behind her I rose quickly, scanning the floor for some sign of the opening through which Gotrah had gone. A furry rug had been drawn aside from the center of the floor, but in the polished black stone I searched in vain for a crevice to denote the hidden trap. I momentarily expected the return of Yasmeena, and my heart pounded within me. Suddenly, under my very hand, a section of the floor detached itself and began to move upward. A pantherish bound carried me behind a tapestried couch, where I crouched, watching the trap rise upward. The narrow head of Gotrah appeared, then his winged shoulders and body.

He climbed up into the chamber, and as he turned to lower the lifted trap, I left the floor with a cat-like leap that carried me over the couch and full on his shoulders.

He went down under my weight, and my gripping fingers crushed the yell in his throat. With a convulsive heave he twisted under me, and stark horror flooded his face as he glared up at me. He was down on the cushioned stone, pinned under my iron bulk. He clawed for the dagger at his girdle, but my knee pinned it down. And crouching on him, I gutted my mad hate for his cursed race. I strangled him slowly, gloatingly, avidly watching his features contort and his eyes glaze. He must have been dead for some minutes before I loosed my hold.

Rising, I gazed through the open trap. The light from the torches of the chamber shone down a narrow shaft, into which was cut a series of narrow steps, that evidently led down into the bowels of the rock Yuthla. From the conversation I had heard, it must lead to the temple of the Akkis, in the town below. Surely I would find Akka no harder to escape from than Yugga. Yet I hesitated, my heart torn at the thought of leaving Altha alone in Yugga. But there was no other way. I did not know in what part of that devil-city she was imprisoned, and I remembered what Gotrah had said of the great band of warriors guarding her and the other virgins.

Virgins of the Moon! Cold sweat broke out on me as the full significance of the phrase became apparent. Just what the festival of the Moon was I did not fully know, but I had heard hints and scattered comments among the Yaga women, and I knew it was a beastly saturnalia, in which the full frenzy of erotic ecstasy was reached in the dying gasps of the wretches sacrificed to the only god the winged people recognized-their own inhuman lust.

The thought of Altha being subjected to such a fate drove me into a berserk frenzy, and steeled my resolution. There was but one chance-to escape myself, and try to reach Koth and bring back enough men to attempt a rescue. My heart sank as I contemplated the difficulties in the way, but there was nothing else to be done.

Lifting Gotrah's limp body I dragged it out of the chamber through a door different from that through which Yasmeena had gone; and traversing a corridor without meeting anyone, I concealed the corpse behind some tapestries. I was certain that it would be found, but perhaps not until I had a good start. Perhaps its presence in another room than the chamber of the trap might divert suspicion from my actual means of escape, and lead Yasmeena to think that I was merely hiding somewhere in Yugga.

But I was crowding my luck. I could not long hope to avoid detection if I lingered. Returning to the chamber, I entered the shaft, lowering the trap above me. It was pitch-dark, then, but my groping fingers found the catch that worked the trap, and I felt that I could return if I found my way blocked below. Down those inky stairs I groped, with an uneasy feeling that I might fall into some pit or meet with some grisly denizen of the underworld. But nothing occurred, and at last the steps ceased and I groped my way along a short corridor that ended at a blank wall. My fingers encountered a metal catch, and I shot the bolt, feeling a section of the wall revolving under my hands. I was dazzled by a dim yet lurid light, and blinking, gazed out with some trepidation.

I was looking into a lofty chamber that was undoubtedly a shrine. My view was limited by a large screen of carved gold directly in front of me, the edges of which flamed dully in the weird light.

Gliding from the secret door, I peered around the screen. I saw a broad room, made with the same stern simplicity and awesome massiveness that characterized architecture. The ceiling was lost in the brooding shadows; the walls were black, dully gleaming, and unadorned. The shrine was empty except for a block of ebon stone, evidently an altar, on which blazed the lurid flame I had noted, and which seemed to emanate from a great somber jewel set upon the altar. I noticed darkly stained channels on the sides of that altar, and on the dusky stone lay a roll of white parchment-Yasmeena's word to her worshippers. I had stumbled into the Akka holy of holies-uncovered the very root and base on which the whole structure of Akka theology was based: the supernatural appearances of revelations from the goddess, and the appearance of the goddess herself in the temple. Strange that a whole religion should be based on the ignorance of the devotees concerning a subterranean stair! Stranger still, to an Earthly mind, that only the lowest form of humanity on Almuric should possess a systematic and ritualistic religion, which Earth people regard as sure token of the highest races!

But the cult of the Akkas was dark and weird. The whole atmosphere of the shrine was one of mystery and brooding horror. I could imagine the awe of the blue worshippers to see the winged goddess emerging from behind the golden screen, like a deity incarnated from cosmic emptiness.

Closing the door behind me, I glided stealthily across the temple. Just within the door a stocky blue man in a fantastic robe lay snoring lustily on the naked stone. Presumably he had slept tranquilly through Gotrah's ghostly visit. I stepped over him as gingerly as a cat treading wet earth, Gotrah's dagger in my hand, but he did not awaken. An instant later I stood outside, breathing deep of the river-laden night air.

The temple lay in the shadow of the great cliffs. There was no moon, only the myriad millions of stars that glimmer in the skies of . I saw no lights anywhere in the village, no movement. The sluggish Akkis slept soundly.

Stealthily as a phantom I stole through the narrow streets, hugging close to the sides of the squat stone huts. I saw no human until I reached the wall. The drawbridge that spanned the river was drawn up, and just within the gate sat a blue man, nodding over his spear. The senses of the Akkis were dull as those of any beasts of burden. I could have knifed the drowsy watchman where he sat, but I saw no need of useless murder. He did not hear me, though I passed within forty feet of him. Silently I glided over the wall, and sil

ently I slipped into the water.

Striking out strongly, I forged across the easy current, and reached the farther bank. There I paused only long enough to drink deep of the cold river water; then I struck out across the shadowed desert at a swinging trot that eats up miles-the gait with which the Apaches of my native Southwest can wear out a horse.

In the darkness before dawn I came to the banks of the Purple River , skirting wide to avoid the watchtower which jutted dimly against the star-flecked sky. As I crouched on the steep bank and gazed down into the rushing swirling current, my heart sank. I knew that, in my fatigued condition, it was madness to plunge into the maelstrom. The strongest swimmer that either Earth or ever bred had been helpless among those eddies and whirlpools. There was but one thing to be done-try to reach the Bridge of Rocks before dawn broke, and take the desperate chance of slipping across under the eyes of the watchers. That, too, was madness, but I had no choice.

But dawn began to whiten the desert before I was within a thousand yards of the Bridge. And looking at the tower, which seemed to swim slowly into clearer outline, etched against the dim sky, I saw a shape soar up from the turrets and wing its way toward me. I had been discovered. Instantly, a desperate plan occurred to me. I began to stagger erratically, ran a few paces, and sank down in the sand near the river bank. I heard the beat of wings above me as the suspicious harpy circled; then I knew he was dropping earthward. He must have been on solitary sentry duty, and had come to investigate the matter of a lone wanderer, without waking his mates.

Watching through slitted lids, I saw him strike the earth near by, and walk about me suspiciously, scimitar in hand. At last he pushed me with his foot, as if to find if I lived. Instantly my arm hooked about his legs, bringing him down on top of me. A single cry burst from his lips, half-stifled as my fingers found his throat; then in a great heaving and fluttering of wings and lashing of limbs, I heaved him over and under me. His scimitar was useless at such close quarters. I twisted his arm until his numbed fingers slipped from the hilt; then I choked him into submission. Before he regained his full faculties, I bound his wrists in front of him with his girdle, dragged him to his feet, and perched myself astride his back, my legs locked about his torso. My left arm was hooked about his neck, my right hand pricked his hide with Gotrah's dagger.

In a few low words I told him what he must do, if he wished to live. It was not the nature of a Yaga to sacrifice himself, even for the welfare of his race. Through the rose-pink glow of dawn we soared into the sky, swept over the rushing Purple River , and vanished from the sight of the land of Yagg , into the blue mazes of the northwest.

Chapter 11

I drove that winged devil unmercifully. Not until sunset did I allow him to drop earthward. Then I bound his feet and wings so he could not escape, and gathered fruit and nuts for our meal. I fed him as well as I fed myself. He needed strength for the flight. That night the beasts of prey roared perilously close to us, and my captive turned ashy with fright, for we had no way of making a protecting fire, but none attacked us. We had left the forest of the Purple River far, far behind, and were among the grasslands. I was taking the most direct route to Koth, led by the unerring instinct of the wild. I continually scanned the skies behind me for some sign of pursuit, but no winged shapes darkened the southern horizon.

It was on the fourth day that I spied a dark moving mass in the plains below, which I believed was an army of men marching. I ordered the Yaga to fly over them. I knew that I had reached the vicinity of the wide territory dominated by the city of Koth , and there was a chance that these might be men of Koth. If so, they were in force, for as we approached I saw there were several thousand men, marching in some order.

So intense was my interest that it almost proved my undoing. During the day I left the Yaga's legs unbound, as he swore that he could not fly otherwise, but I kept his wrists bound. In my engrossment I did not notice him furtively gnawing at the thong. My dagger was in its sheath, since he had shown no recent sign of rebellion. My first intimation of revolt was when he wheeled suddenly sidewise, so that I lurched and almost lost my grip on him. His long arm curled about my torso and tore at my girdle, and the next instant my own dagger gleamed in his hand.

There ensued one of the most desperate struggles in which I have ever participated. My near fall had swung me around, so that instead of being on his back, I was in front of him, maintaining my position only by one hand clutching his hair, and one knee crooked about his leg. My other hand was locked on his dagger wrist, and there we tore and twisted, a thousand feet in the air, he to break away and let me fall to my death, or to drive home the dagger in my breast, I to maintain my grip and fend off the gleaming blade.

On the ground my superior weight and strength would quickly have settled the issue, but in the air he had the advantage. His free hand beat and tore at my face, while his unimprisoned knee drove viciously again and again for my groin. I hung grimly on, taking the punishment without flinching, seeing that our struggles were dragging us lower and lower toward the earth.

Realizing this, he made a final desperate effort. Shifting the dagger to his free hand, he stabbed furiously at my throat. At the same instant I gave his head a terrific downward wrench. The impetus of both our exertions whirled us down and over, and his stroke, thrown out of line by our erratic convulsion, missed its mark and sheathed the dagger in his own thigh. A terrible cry burst from his lips, his grasp went limp as he half fainted from the pain and shock, and we rushed plummetlike earthward. I strove to turn him beneath me, and even as I did, we struck the earth with a terrific concussion.

From that impact I reeled up dizzily. The Yaga did not move; his body had cushioned mine, and half the bones in his frame must have been splintered.

A clamor of voices rang on my ears, and turning, I saw a horde of hairy figures rushing toward me. I heard my own name bellowed by a thousand tongues. I had found the men of Koth.

A hairy giant was alternately pumping my hand and beating me on the back with blows that would have staggered a horse, while bellowing: "Ironhand! By Thak's jawbones, *Ironhand*! Grip my hand, old war-dog! Hell's thunders, I've known no such joyful hour since the day I broke old Khush of Tanga's back!"

There was old Khossuth Skullsplitter, somber as ever, Thab the Swift, Gutchluk Tigerwrath-nearly all the mighty men of Koth. And the way they smote my back and roared their welcome warmed my heart as it was never warmed on Earth, for I knew there was no room for insincerity in their great simple hearts.

"Where have you been, Ironhand?" exclaimed Thab the Swift. "We found your broken carbine out on the plains, and a Yaga lying near it with his skull smashed; so we concluded that you had been done away with by those winged devils. But we never found your body-and now you come tumbling through the skies locked in combat with another flying fiend! Say, have you been to Yugga?" He laughed as a man laughs when he speaks a jest.

"Aye to Yugga, on the rock Yuthla, by the river Yogh, in the land of Yagg ," I answered. "Where is Zal the Thrower?"

"He guards the city with the thousand we left behind," answered Khossuth.

"His daughter languishes in the Black City ," I said. "On the night of the full moon, Altha, Zal's daughter, dies with five hundred other girls of the Guras-unless we prevent it."

A murmur of wrath and horror swept along the ranks. I glanced over the savage array. There were a good four thousand of them; no bows were in evidence, but each man bore his carbine. That meant war, and their numbers proved it was no minor raid.

"Where are you going?" I asked.

"The men of Khor move against us, five thousand strong," answered Khossuth. "It is the death grapple of the tribes. We march to meet them afar off from our walls, and spare our women the horrors of the war."

"Forget the men of Khor!" I cried passionately. "You would spare the feelings of your women-yet thousands of your women suffer the tortures of the damned on the ebon rock of Yuthla! Follow me! I will lead you to the stronghold of the de

vils who have harried for a thousand ages!"

"How many warriors?" asked Khossuth uncertainly.

"Twenty thousand."

A groan rose from the listeners.

"What could our handful do against that horde?"

"I'll show you!" I exclaimed. "I'll lead you into the heart of their citadel!"

"Hai!" roared Ghor the Bear, brandishing his broadsword, always quick to take fire from my suggestions. "That's the word! Come on, sir brothers! Follow Ironhand! He'll show us the way!"

"But what of the men of Khor?" expostulated Khossuth. "They are marching to attack us. We must meet them."

Ghor grunted explosively as the truth of this assertion came home to him and all eyes turned toward me.

"Leave them to me," I proposed desperately. "Let me talk with them-"

"They'll hack off your head before you can open your mouth," grunted Khossuth.

"That's right," admitted Ghor. "We've been fighting the men of Khor for fifty thousand years. Don't trust them, comrade."

"I'll take the chance," I answered.

"The chance you shall have, then," said Gutchluk grimly. "For there they come!" In the distance we saw a dark moving mass.

"Carbines ready!" barked old Khossuth, his cold eyes gleaming. "Loosen your blades, and follow me."

"Will you join battle tonight?" I asked. He glanced at the sun. "No. We'll march to meet them, and pitch camp just out of gunshot. Then with dawn we'll rush them and cut their throats."

"They'll have the same idea," explained Thab. "Oh, it will be great fun!"

"And while you revel in senseless bloodshed," I answered bitterly, "your daughters and theirs will be screaming vainly under the tortures of the winged people over the river Yogh. Fools! Oh, you fools!"

"But what can we do?" expostulated Gutchluk.

"Follow me!" I yelled passionately. "We'll march to meet them, and I'll go on to them alone."

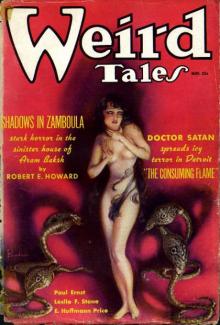

Shadows in Zamboula (conan the barbarian)

Shadows in Zamboula (conan the barbarian) Shadows in the Moonlight (conan the barbarian)

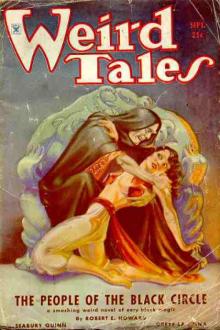

Shadows in the Moonlight (conan the barbarian) The People of the Black Circle (conan the barbarian)

The People of the Black Circle (conan the barbarian) Almuric

Almuric Xuthal of the Dusk (conan the barbarian)

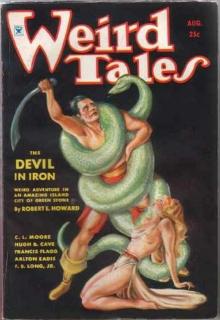

Xuthal of the Dusk (conan the barbarian) The Devil in Iron (conan the barbarian)

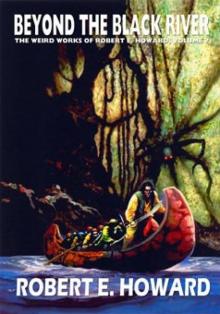

The Devil in Iron (conan the barbarian) Beyond the Black River (conan the warrior)

Beyond the Black River (conan the warrior) The Phoenix on the Sword (conan the barbarian)

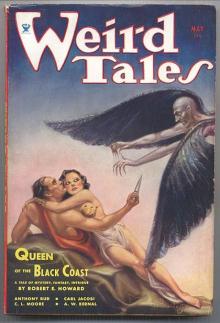

The Phoenix on the Sword (conan the barbarian) Queen of the Black Coast

Queen of the Black Coast The Tower of the Elephant (conan the barbarian)

The Tower of the Elephant (conan the barbarian) Black Colossus

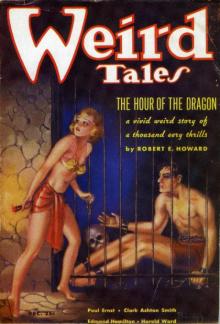

Black Colossus The Hour of the Dragon (conan the barbarian)

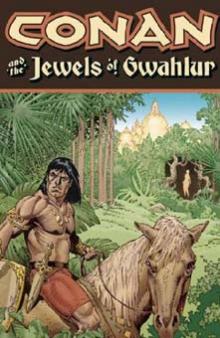

The Hour of the Dragon (conan the barbarian) Jewels of Gwahlur (conan the warrior)

Jewels of Gwahlur (conan the warrior) Gods of the North (conan the barbarian)

Gods of the North (conan the barbarian) The Pool of the Black One (conan the barbarian)

The Pool of the Black One (conan the barbarian) A Witch Shall Be Born

A Witch Shall Be Born Red Nails (conan the warrior)

Red Nails (conan the warrior)